J.R. Montgomery is not a household name. Yet.

J.R. Montgomery is not a household name. Yet.

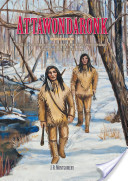

His first book, however, is ground-breaking for its telling of the Attawondaronks who lived in Southern Ontario at the beginning of the sixteenth century. And Rick adds to the excitement with his story of a life-long preoccupation with these early peoples, so much so that he is an authority on the topic.

I have known Rick for many years but I never knew about his writing or his interest in history, two interests that we definitely share. Today I take great pleasure in giving my readers the gift of a new historical author about whom we shall definitely hear more.

EC: People often want to know how long the writing of a book takes. Would you discuss that but include all the work and research that went on before you ever started writing, perhaps even telling the story of how you became interested in this topic?

JRM: I became interested in the first inhabitants of Southern Ontario as a young boy, when I found three rock-covered graves in a walnut grove on our family farm. They should not have been there as no towns or settlements have ever been found within miles of the hillside where these people were buried. This mystery led me to read everything I could find about the Attawondaronks and other First Nations peoples of North America.

Thus my research for the story “Attawondaronk” has really been a lifetime of fun and discovery. The actual writing of the story took a year … a time during which my home office was full of open books for quick factual references on a multitude of topics.

EC: What is the derivation of the title, Attawondaronk, and how did you settle on this for your title?

JRM: These people were referred to by many names, such as, Attawondaron, Petuns, and Neutrals, to name a few. I settled on the Sennikae name for them, which was Attawondaronk. The Sennikae (known today as Seneca) play a very significant role in this story. In the Iroquoian language, Attawondaronk means “talks crooked.” So … even though each nation spoke the same language, the Sennikae felt that the Attawondaronks had a decidedly strong accent and were a bit hard to understand.

EC: Your novel begins in 1538 with tribes in the land which is today Southern Ontario. How plentiful was research material for this time period?

JRM: The Attawondaronks were only visited for a few days by Europeans, so firsthand knowledge of this culture is limited to a few inaccurate maps and brief accounts by Jesuit priests. The Attawondaronks disappeared shortly after these visits. Thus, most of what is known today has been gleaned from the archaeological record – the artifacts and items of everyday use that they left behind. For those wishing to learn more of how these people lived, “The Archaeology of Southern Ontario to AD 1650” is a wealth of information.

EC: You include a list of the main characters and the towns at the beginning of the book. How original are those which you have picked? Did you find them in your research or are some your creation?

JRM: The Jesuit accounts by Brebeuf and Chaumonot give some names of towns and leaders at the time of their visit, and Nicholas Samson’s map of 1656 names towns and rivers, but the locations that he showed were terribly inaccurate. Ounontisaston (Lawson site) and Tontiaton (Southwold Earthworks) have been found and excavated … you can visit these sites in London and St.Thomas today. The sites that have not been located, I placed along rivers where I felt they could best control the territory against enemy incursions. I used the known names of towns, rivers and people, wherever possible. Only a handful of the character names are actual recorded names however, the majority coming from my imagination and my pen.

EC: The shamans are not shown in a very positive light in Attawondaronk. Have you had any reaction to this? Did you find historical evidence to support this characterization or is this part of the author’s imagination, given the historical facts at hand?

JRM: I have had one person who felt I was a bit heavy-handed with the shamans. In reading about ancient societies and First Nation peoples however, it is fairly obvious that shamans all down through time have used spiritual beliefs to bend people to their own wills, and generally for their own benefit. This is not just an historical phenomenon, but still goes on today with people like Jim Jones and David Koresh. No-one today can be certain just how much control the Attawondaronk shamans really held over their people. The shamans were very useful however, as malevolent antagonists, allowing me to reveal the unusual beliefs and rituals of the Attawondaronks.

EC: The point of view shifts in your book. Can you tell us how you decided on point of view and what problems you had with this shifting from inside one character’s thoughts to another’s? Did you consider any rules such as starting a new section or chapter when a new POV was used?

JRM: I used scene breaks whenever I shifted the story to another person’s actions or thoughts. The reader needs to know what is going on in other people’s minds. Even when getting into someone else’s head … such as Poutassa’s … can be somewhat disturbing. Frankly, I never considered rules for this, but simply wrote as the story came to me.

EC: Is the map of present-day Ontario at the beginning of the book accurate as to rivers and lakes? How necessary do you think the maps are to the reader in historical fiction?

JRM: Yes, the rivers and lakes have not changed much, and if you look at a modern map you will be able to see that the Tranchi is today’s Thames River, and the Kandia is now known as the Grand. I like to have maps in historical books that I read so that I can visualize the location of each scene. In Attawondaronk, I wanted the reader to be able to take a modern-day map and see exactly where the towns are located, not only to visualize the local, but to go and visit the site if they want. In the case of Ounontisaston for instance, you can go and stand on the bluff and see the Entry River, and Snake Creek, almost exactly as Taiwa and Sounia saw them almost 500 years ago. (The rivers are about 50 % smaller today than they were in 1538.)

EC: What was your experience with getting your book published? Will you continue to use iUniverse?

JRM: Publishing for a first-time author is an exercise in frustration. iUniverse is discussing the second book with me, but I haven’t made a final decision yet. iUniverse has just been purchased by Penguin, so their approach to authors is bound to change.

EC: I know the story goes on from the end of Attawondaronk. How many books are in the series and are they written or still in the planning stages?

JRM: Attawondaronk is a trilogy. The second book “The Reckoning” is written and undergoing its first edit. Book number three is still in my head.

EC: What has been the hardest part of creating this wonderful book? Have you learned things that will make the next one easier?

JRM: The writing was the easy part – and the most fun. I have learned so much through this process, I couldn’t begin to discuss it all … except to say with confidence, that next time will be much easier. The editing and proofreading by the publisher seemed to go on forever, back and forth constantly as the author must approve and agree with all changes. We actually had more trouble with the covers than any other part of the process. The covers took three months to lay out to everyone’s satisfaction.

EC: Is there anything else you think my readers might like to know about your writing and your books?

JRM: Attawondaronk is a story of a lost and almost forgotten people. The story follows a family who try to change the direction that their nation is taking, and what happens to them for their efforts. As we follow this family’s ordeals, the daily lives, spiritual beliefs, and rituals of this fascinating culture come to life. A story of courage, romance, betrayal and revenge … when you finish Attwondaronk, you will know more about Southern Ontario’s first nation than most scholars.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Born in 1953, J.R. Montgomery grew up on a small farm in Southern Ontario. At an early age he found three archaic graves and several artifacts on the property. In subsequent years he became an avid student of the first inhabitants of the Americas.

He still resides in rural Ontario, and has studied the known archaeological sites brought to life in this story. He has written articles and short stories for local newspapers and hang gliding publications. Attawondaronk is his first novel.

Consider leaving a comment below to connect with Rick or myself.

Click here to buy Attawondaronk.

Click here to download A Free Giveaway of Tips for Writers! by Elaine Cougler

Enjoyed reading about another historical author’s pathway to publication.

LikeLike

So glad, Gay. Thanks for commenting here. Merry Christmas!

LikeLike

JR, one of the aspects of researching historical pieces that I enjoy is seeing how the maps have changed. Noting the towns that have been established and the cities that have grown over the intervening years is expected, but to note the change in the size of lakes is quite something.

LikeLike

And Rick’s book is full of excellent research which illuminates a compelling plot. Didn’t know you wrote historicals, too, Sherry. Good for you.

LikeLike

Congratulations to Rick on getting that first book out there, and to Elaine, great interview.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Robert, for the kind words. I’m glad you enjoyed reading about J.R. Montgomery!

LikeLike

This was a very interesting interview. I enjoyed reading J.R’s thoughts on his research and novel. I’m in awe of historical authors.

LikeLike

Thanks, Brinda. I am in awe of all you do, as well.

LikeLike

Hi J.R.,

I learned quite a bit just from this interview. I’m sure that the book is incredibly informative and the plot sounds interesting too. Congrats on your first book!

LikeLike

Hi Jessica! Thanks for commenting. Merry, Merry Christmas.

LikeLike

Hey Elaine, great interview and an interesting subject.

Cheers

Laurie

LikeLike

Thanks, Laurie. Good to have you visit!

LikeLike

I find it so interesting that Attawondaronk means, “talks crooked”, according to the Iroquoi language. J.R. mentioned that there are several names for this amazing group of people, but it made me wonder what they might have called themselves. It’s the little mysterious surrounding these all-but-forgotten groups throughout history that I find so fascinating. Congratulations to J.R. on all his wonderful research! Great interview, Elaine!

LikeLike